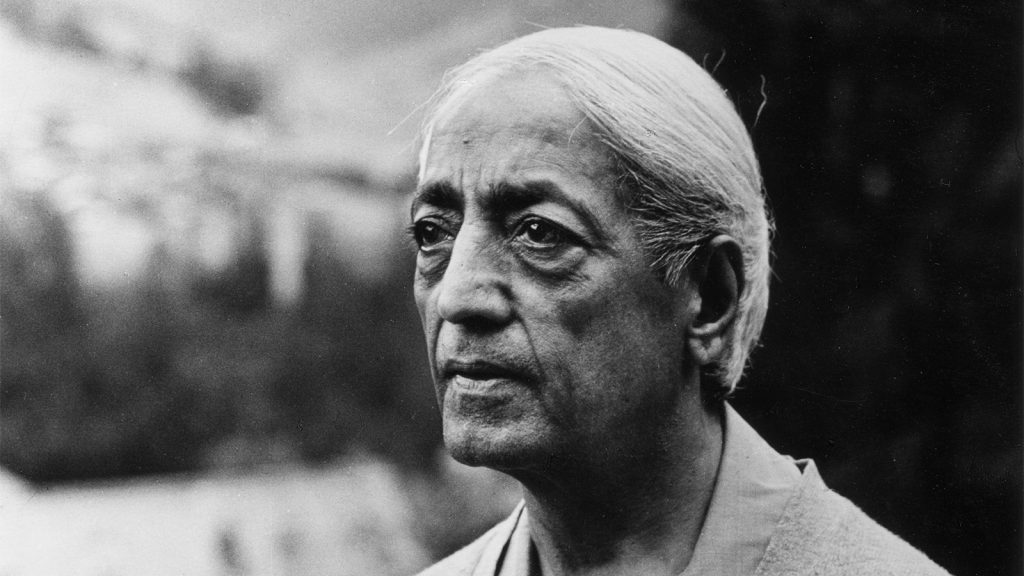

Jiddu Krishnamurti Life & Biography

Birth and Family Background

Jiddu Krishnamurti was born on May 12,1895, in the small town of Madanapalle, nestled in the Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh, India. His birth coincided with the austere simplicity of a Brahmin household, where tradition wove itself into every detail of daily life. The family revered the ancient Vedic rituals, their lives colored by a quiet religiosity that permeated the air like the smell of incense during morning prayers.

Krishnamurti was the eighth child of Jiddu Narayaniah and Sanjeevamma, a position of symbolic significance in superstition. In a culture where numbers, birth positions, and omens dictated one’s destiny, the eighth child was often seen as harboring special potential or spiritual resonance. Krishnamurti’s father, Narayaniah, worked as a clerk in the British colonial administration, a position of relative stability yet fraught with subservience.

His work brought the family into the orbit of the colonial elite, exposing young Krishnamurti to both the rigidity of tradition and the dominance of the British Empire. His mother, Sanjeevamma, was deeply religious, a woman whose spirituality transcended the rote performance of rituals. She believed in visions and mystical experiences, planting early seeds of wonder in Krishnamurti’s impressionable mind.

When Krishnamurti was just ten years old, his mother passed away. This loss created a void that would echo throughout his life, leaving him to a longing that no relationship or philosophy could fully satisfy. The maternal bond, with its intimacy, was severed, leaving him to grapple with an early sense of impermanence—a lesson that life’s stability is as fleeting as morning dew.

Discovery by the Theosophical Society

The defining moment of Krishnamurti’s early life came in 1909, on the sandy banks of the Adyar River in Chennai. By then, the family had relocated to the vicinity of the Theosophical Society’s headquarters. Narayaniah, recently retired, had taken up a minor clerical role within the society, an organization dedicated to the synthesis of Eastern and Western spiritual traditions.

It was here, on an unremarkable afternoon, that Charles Webster Leadbeater, a prominent Theosophist, encountered the young boy. Krishnamurti was a fragile, poorly dressed child with an absentminded demeanor. Leadbeater’s initial impression was hardly flattering—he thought the boy was unkempt and unintelligent. However, something extraordinary occurred during that encounter: Leadbeater claimed to perceive an aura of remarkable purity surrounding Krishnamurti, untouched by selfishness or conflict. This aura, according to Leadbeater, marked him as a spiritual vessel of extraordinary potential.

The discovery of Krishnamurti became the centerpiece of Theosophical discourse almost overnight. Annie Besant, then the President of the Theosophical Society, was informed of this “world-changing” find. Besant, a woman of immense charisma and vision, became deeply invested in Krishnamurti’s development. She and Leadbeater declared that Krishnamurti was the physical vehicle for the manifestation of the “World Teacher,” a messianic figure prophesied to guide humanity into a new spiritual era.

The Adoption and Theosophical Training

Krishnamurti’s father, initially skeptical of these claims, eventually relinquished custody of the boy to Besant and Leadbeater. This decision would uproot Krishnamurti, immersing him instead in the esoteric world of Theosophy. He and his younger brother Nitya were moved into the opulent surroundings of the Theosophical headquarters, where they were isolated from their peers and subjected to rigorous training.

This period marked a radical transformation in Krishnamurti’s life. From a village boy who wandered barefoot along dusty paths, he was suddenly thrust into an environment filled with Western intellectuals and scholars. His days were regimented with study, meditation, and preparation. He was tutored in English and classical literature. Every aspect of his life was meticulously curated to mold him into the spiritual figure the Theosophists believed him to be.

Yet, the young Krishnamurti was far from the ideal candidate for this role. By his own admission in later years, he struggled academically, his mind resistant to the memorization that formal education demanded. More poignantly, he lacked the self-awareness or spiritual gravitas expected of the “World Teacher.” Accounts from this time describe him as shy, introverted, and emotionally dependent on his younger brother, Nitya.

Nevertheless, Besant and Leadbeater persisted. Their vision for Krishnamurti was not shaped by his current capabilities but by what they believed he could become. They saw him as a blank slate, an empty vessel, ready to be filled with divine purpose.

The Order of the Star in the East

In 1911, the Theosophists formalized their vision for Krishnamurti’s role by establishing the Order of the Star in the East. This organization functioned as the vehicle through which the World Teacher’s message would be disseminated. Krishnamurti was placed at the center of the Order, his name increasingly associated with spiritual authority.

The Theosophists spared no effort in building Krishnamurti’s global image. Public meetings were organized and resources were poured into promoting the coming of the World Teacher. Krishnamurti himself was brought to Europe, where he was introduced to aristocrats and spiritual seekers. He spent summers in the Alps and winters in England, his life oscillating between periods of intense preparation and exposure to the world’s elite.

To the casual observer, this seemed like the life of privilege and purpose. Yet, beneath the surface, cracks began to form. Krishnamurti was deeply attached to his brother Nitya, and the two shared a bond that transcended the rigid roles assigned to them by Theosophy. Nitya served as both a confidant and an emotional anchor for Krishnamurti, offering him normalcy amidst the whirlwind of expectations.

The Struggles of a Spiritual Prodigy

Despite the grandeur surrounding his role, Krishnamurti’s personal experiences during this time were marked by inner turmoil. The spiritual training imposed upon him often felt like a burden rather than a calling. Leadbeater’s insistence on strict discipline clashed with Krishnamurti’s natural disposition, which leaned toward introspection and quiet observation.

Moreover, the Theosophists’ claims about his divine destiny conflicted with his personal sense of inadequacy. Krishnamurti later described these years as being filled with doubt and confusion. He found himself caught between two worlds: the ordinary humanity of his childhood and the extraordinary expectations of his Theosophical guardians. This tension would eventually become a central theme in his teachings, where he urged others to abandon the false dichotomies imposed by society and to embrace life as it is.

Emerging Signs of Transformation

Amidst these struggles, there were moments of transformation. The turning point in Krishnamurti’s inner journey came in 1922, during a retreat in Ojai, California. There, he underwent what has often been described as a spiritual awakening or a mystical experience. Accounts vary, but Krishnamurti himself referred to this period as a time of intense physical and psychological upheaval.

He described a “process” that began with severe pain at the base of his spine, spreading upward through his body and culminating in a sense of transcendence. This experience, while not entirely understood, marked the beginning of his liberation from the constructs imposed upon him by Theosophy. It was as if the layers of expectation, doctrine, and conditioning began to dissolve, leaving behind a direct, unmediated relationship with existence.

This event set the stage for Krishnamurti’s eventual renunciation of the Theosophical framework. It planted the seeds of his unique philosophy, which rejected all authority—spiritual, psychological, or institutional—and emphasized the necessity of personal freedom and self-inquiry.

Reflection on Early Life

Krishnamurti’s early life was a period of intense preparation, where the forces of tradition, mysticism, and modernity collided. Yet, it was also a time of deep personal struggle, marked by loss, alienation, and the weight of expectations.

This phase of his life serves as a reminder that the spiritual journey often begins not in clarity but in confusion. Krishnamurti’s eventual liberation was forged in the fires of these early experiences, teaching us that even the most extraordinary destinies are rooted in the ordinariness of human struggle. The boy from Madanapalle, once dismissed as frail and unremarkable, was already on a path that would lead him to shatter the very foundations of spiritual authority.

The Turning Point: Awakening and Renunciation

The Death of Nitya

The death of Nitya, Jiddu Krishnamurti’s younger brother, in 1925 was the pivotal event that shattered his reliance on Theosophical doctrines and altered his spiritual trajectory. The brothers had shared an intimate bond that transcended the ordinary connection of siblings. Nitya was not only Krishnamurti’s confidant and emotional anchor but also his companion through the surreal labyrinth of expectations imposed by the Theosophical Society.

In the early 1920s, both Krishnamurti and Nitya had traveled to Europe to fulfill the growing demands of the Order of the Star in the East. Nitya, however, had been suffering from tuberculosis, and his health deteriorated rapidly. The Theosophists, including Annie Besant, assured Krishnamurti that Nitya’s survival was certain. They claimed that the spiritual forces protecting the Order would intervene.

When Nitya succumbed to his illness on November 13, 1925, the blow was catastrophic. Krishnamurti, who had been relying on Theosophical assurances, was devastated. His grief was not only for the loss of his beloved brother but also for the collapse of the spiritual framework that had been imposed upon him. The promises of divine intervention had failed.

In the days and months that followed, Krishnamurti retreated into deep introspection. He later described this period as a deep awakening, though it was not one of comfort or solace. Instead, it was a confrontation with the raw reality of life, stripped of comforting illusions. The death of Nitya marked the moment when Krishnamurti began to question everything he had been taught, everything he had been made to believe. It was the death of certainty.

The Dissolution of the Order of the Star in the East

The culmination of Krishnamurti’s growing disillusionment came in 1929 when he formally renounced the Theosophical framework and dissolved the Order of the Star in the East. This decision was revolutionary. The Order had grown into a massive global organization, with tens of thousands of members and significant resources devoted to promoting Krishnamurti as the World Teacher. In a historic speech delivered at the Order’s annual gathering in Ommen, Netherlands, Krishnamurti declared:

“I maintain that Truth is a pathless land, and you cannot approach it by any path whatsoever, by any religion, by any sect. That is my point of view, and I adhere to that absolutely and unconditionally.”

The dissolution of the Order was not just an administrative decision; it was a profound shift in philosophy. By rejecting the authority placed upon him and the structures created around his role, Krishnamurti affirmed the importance of individual freedom over institutionalized spirituality. He questioned the very foundations of organized religion and spiritual hierarchies, emphasizing that no teacher, no guru, and no system could lead one to Truth.

This act of renunciation shocked the Theosophical Society and its followers. Many felt betrayed and struggled to understand how the man they had nurtured and revered could so decisively reject their efforts. For Krishnamurti, though, it was not an act of rebellion but of necessity. He realized that true freedom lies beyond the boundaries of belief and authority.

A Spiritual Awakening in Ojai

Krishnamurti’s spiritual awakening, often called “The Process,” began in 1922 during his time in Ojai, California. It was a mysterious and transformative experience that became a defining moment in his journey toward self-realization.

The “Process” involved both physical and psychological sensations. Krishnamurti described an intense, searing pain at the base of his spine, which seemed to rise upward through his body. This culminated in a profound sense of unity and clarity, accompanied by deep, unshakable silence. He described feeling the dissolution of his ego, as if he were no longer bound by any sense of self.

In his own words:

“There was an intense vitality, not of physical energy but of an inner, deep feeling. I was supremely happy, for I had seen. Nothing could ever be the same.”

This awakening wasn’t tied to any specific religious or mystical tradition. Krishnamurti rejected interpretations that linked it to kundalini, enlightenment, or divine intervention. For him, it was a direct encounter with life’s totality, free from the constraints of thought and identity.

The Ojai experience marked a turning point. From that moment, Krishnamurti began speaking from direct insight rather than repeating the doctrines he had learned. His teachings, which once reflected Theosophical ideas, became deeply original and rooted in immediate observation, entirely rejecting dogma.

Freedom from Authority

Krishnamurti’s awakening and his renunciation of the Order stemmed from a single, powerful realization: freedom is the essence of spiritual life. He saw that authority—both external and internal—was the greatest obstacle to this freedom.

External authorities, such as religious institutions, political ideologies, and cultural norms, condition the mind and limit perception. Internal authorities, like beliefs, memories, and psychological patterns, create a false sense of identity and security. Together, these forms of authority trap individuals in cycles of fear and dependence.

Krishnamurti’s message was clear: to understand the truth, one must reject all authority. This didn’t mean embracing anarchy or chaos, but adopting a radical openness to life as it is. He stressed the importance of direct perception, free from the filters of thought and tradition.

“To be free is not to rebel against authority but to understand it, to see it for what it is and, in that understanding, to transcend it.”

Rejection of Gurus and Systems

One of the most striking aspects of Krishnamurti’s teachings was his rejection of the guru-disciple relationship. He believed this dynamic was inherently hierarchical and created dependence rather than liberation. For him, following a guru was tantamount to surrendering one’s responsibility for self-discovery.

“The moment you follow someone, you cease to follow Truth.”

Krishnamurti extended his critique to all systems of thought, including religion, philosophy, and psychology. He saw these systems as constructs of the mind—attempts to impose order on life’s inherent chaos. However, in doing so, they limited perception and perpetuated conflict.

This rejection of systems was not a denial of inquiry or exploration. Instead, it was an invitation to engage with life directly, without the interference of preconceptions or ideologies.

A Pathless Land

The phrase “Truth is a pathless land” became the foundation of Krishnamurti’s teachings. It expressed his belief that truth cannot be approached through fixed methods, rituals, or beliefs. Paths are finite and structured; they prescribe direction and impose boundaries. Truth, on the other hand, is limitless and cannot be contained within any framework.

Krishnamurti encouraged his audience to abandon the search for truth as an external goal. Instead, he urged them to observe their minds and watch how thoughts and emotions arise. This observation, when free of judgment or resistance, reveals the conditioned nature of the self and opens the door to freedom.

“You must begin to understand yourself—not according to a system, not according to some philosopher or saint, but as you are.”

The Ripple Effect of Renunciation

Krishnamurti’s rejection of the Order and authority had deeper consequences. It freed him from the structures that sought to define him, enabling him to speak authentically. At the same time, it left many followers disillusioned.

Theosophists who had devoted themselves to the idea of Krishnamurti as the World Teacher had to confront the possibility that their beliefs were illusions. Some felt betrayed, while others saw this as an opportunity for deeper reflection.

This renunciation also established Krishnamurti as a unique figure in modern spirituality. Unlike other teachers who built movements or institutions, Krishnamurti remained fiercely independent. He refused to create a school of thought, insisting that his teachings were not doctrines to be followed but tools for self-reflection.

The Essence of Renunciation

At its heart, Krishnamurti’s renunciation was an act of honesty. It was a refusal to compromise with falsehood, a declaration that truth cannot be institutionalized or commodified. Though painful and isolating, this act became the foundation of his later teachings, inspiring millions to question their assumptions about thought, self, and reality.

By stepping away from the structures that sought to define him, Krishnamurti demonstrated that liberation begins with courage—the courage to face the unknown. Freedom is not the result of following a path or adhering to a system but arises from stepping into life’s vastness without fear or expectation.

“Renunciation is not the giving up of things of the world. It is the renunciation of the ego, of the ‘me’ and ‘mine.’”

In dissolving the Order, Krishnamurti embodied this renunciation. This decision set the stage for a life not centered on teaching as a profession but on sharing a vision of freedom that transcends all boundaries. This turning point revealed Krishnamurti as the figure we know today—not a guru or a leader, but a fellow traveler on the pathless journey of existence.

The Wanderer and Independent Philosopher

Years of Teaching: A Life of Travel and Dialogue

After dissolving the Order of the Star in the East, Krishnamurti embraced a life of complete independence. For decades, he traveled across continents, delivering talks, holding dialogues, and engaging with individuals who sought clarity in the chaos of life. From the hills of India to the salons of Europe, from packed auditoriums in the United States to quiet retreats in Australia, Krishnamurti’s presence left an indelible mark on those who encountered him.

Unlike traditional teachers, Krishnamurti rejected titles, disciples, and any form of organized followership. He did not offer a structured philosophy or a roadmap to enlightenment. Instead, he posed penetrating questions, encouraging his listeners to explore their own minds and lives. His talks were explorations, not lectures. They often began with a deep silence, an invitation for the audience to quiet their inner noise and simply observe.

Krishnamurti’s audiences were diverse—scientists, spiritual seekers, philosophers, and everyday individuals. What united them was an unspoken longing for truth and freedom. Through his words, Krishnamurti gently dismantled the walls of belief, identity, and ideology that confined their minds.

“You must understand the whole of life, not just one little part of it. That is why you must look at the sky, listen to the birds, and feel the earth beneath your feet. Life is everywhere—observe it with openness.”

Krishnamurti’s teaching was radical in its simplicity: live fully in the present by seeing life as it truly is, without filters or distortions.

Core Themes of Krishnamurti’s Teachings

Freedom from Conditioning

Krishnamurti emphasized that the human mind is deeply conditioned by culture, religion, family, and personal experiences. This conditioning creates a limited and fragmented sense of self, which is the root of conflict. To see the truth, one must first become aware of and free from these layers of conditioning.

“The moment you see how conditioned you are, freedom begins.”

The Nature of Fear

Fear, Krishnamurti argued, is one of humanity’s greatest burdens. It arises from attachment to the past and anxiety about the future. Fear binds individuals to patterns of avoidance and control, preventing them from fully living. Only by directly facing and understanding fear can one transcend it.

The Illusion of the Self

Krishnamurti taught that the self, as most people know it, is a construct—a collection of memories, experiences, and desires. This false sense of self creates separation, leading to conflict within and between individuals. Freedom comes from seeing through this illusion.

Observation Without Judgment

Krishnamurti urged people to observe their thoughts, emotions, and actions without judgment. This pure observation reveals the truth of one’s inner and outer worlds, untainted by preconceived notions or interpretations.

“In the space between two thoughts lies the infinite.”

The Pathless Journey

The idea that “Truth is a pathless land” encapsulates Krishnamurti’s rejection of methods, systems, and practices aimed at attaining enlightenment. Truth is not a destination to be reached through effort; it is a living reality, accessible in the present moment to those who look without seeking.

Collaboration with Scientists and Thinkers

Krishnamurti’s dialogues often extended beyond spiritual seekers to include scientists, philosophers, and artists. These conversations bridged the gap between spirituality and intellectual inquiry, offering fresh perspectives on the nature of consciousness and existence.

One of his most significant collaborators was the quantum physicist David Bohm. Together, they delved into the limitations of thought, the nature of perception, and the possibility of a universal mind. Their discussions, documented in The Ending of Time, reflected an unusual synergy between Bohm’s scientific precision and Krishnamurti’s intuitive depth.

These interactions demonstrated how Krishnamurti’s insights resonated beyond traditional spirituality. His ideas on the conditioned mind, the fragmentation of thought, and the need for holistic awareness paralleled breakthroughs in modern psychology and quantum physics.

Schools and Foundations: The Seeds of Inquiry

Though Krishnamurti rejected institutional authority, he saw immense value in education as a means of fostering freedom and understanding. He believed that children, if nurtured in an environment of inquiry and compassion, could grow without the conditioning that binds adults.

Krishnamurti founded several schools around the world, including Rishi Valley School in India, Brockwood Park School in England, and Oak Grove School in California. These schools focused on holistic education, integrating academics with an emphasis on self-awareness and connectedness to nature.

Krishnamurti often visited these schools, engaging in dialogues with students and teachers. His presence emphasized that education was not merely about acquiring knowledge but about understanding life in its totality.

The Krishnamurti Foundations, established in India, the United States, and England, continue to preserve and share his teachings through archives, publications, and digital platforms.

Final Years: A Quiet but Powerful Presence

In his later years, Krishnamurti’s life became quieter but no less impactful. He spent much of his time in Ojai, California, where he found peace in the hills and orchards. His talks during this period carried deep stillness, reflecting the depth of his insights.

Despite his global influence, Krishnamurti lived simply. He avoided fame, choosing instead to live as an ordinary man. He cooked his meals, walked in nature, and remained humble, refusing to let any cult of personality form around him.

His final public talk, delivered in Madras (now Chennai) in January 1986, was as clear and direct as his first. He continued to challenge his listeners to look within, to observe their minds, and to live without fear. Krishnamurti passed away on February 17, 1986, in Ojai, leaving behind no dogma or successor, only his timeless teachings.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Krishnamurti’s influence is vast, yet it defies categorization. He did not create a religion or build a movement, but his teachings continue to inspire spiritual seekers, psychologists, educators, and scientists.

Impact on Modern Spirituality

In a world disillusioned with organized religion, Krishnamurti’s rejection of dogma resonates deeply. His message of self-inquiry and freedom from authority offers a path for those seeking clarity in a fragmented world.

Contributions to Psychology and Education

Krishnamurti’s insights into the conditioned mind have influenced modern psychology, particularly in the fields of mindfulness and cognitive science. His ideas on holistic education continue to shape progressive approaches to teaching.

A Timeless Vision

Krishnamurti’s teachings remain as relevant today as they were during his lifetime. In a world consumed by division, fear, and ideology, his call to live with clarity and freedom offers a way to transcend the noise.

6 Responses

Reading Krishnamurti’s words feels like standing barefoot in an early morning fog, with everything familiar but strangely transparent. I find myself pulled between wanting answers and realizing there may be nothing to grasp at all. His talks make the old walls in my mind a bit shaky, which I never expect or even notice until a long while later. There’s relief in seeing this cycle, but also an odd ache somewhere you can’t quite name.

Sometimes I find myself circling around the same questions, like a leaf spinning gently in the current, never quite landing anywhere solid. Reading this just took me back to nights on my old balcony, wrestling with the restless urge to resolve something inside but unable to put it into words. Doubt and clarity chase each other in circles. There’s both comfort and unease in that, I guess.

Krishnamurti does not hand me a system to follow, which is both relieving and unnerving, but he points again and again to a stillness that is right inside the noise. I caught myself today staring at the movement of leaves outside and realizing for a small moment that the inner chatter paused.

Krishnamurti’s break from Theosophy shatters comfort zones. He faced loss and doubt head on. His life shows freedom means dropping every role imposed on you.

I’ve noticed my mind clings to labels until I simply watch thoughts as they pass. In that space I find real quiet.

He rejected every role to free his mind. He let go of his past and his orders. His example stands firm. One learns to see truth without a map. That is real change.